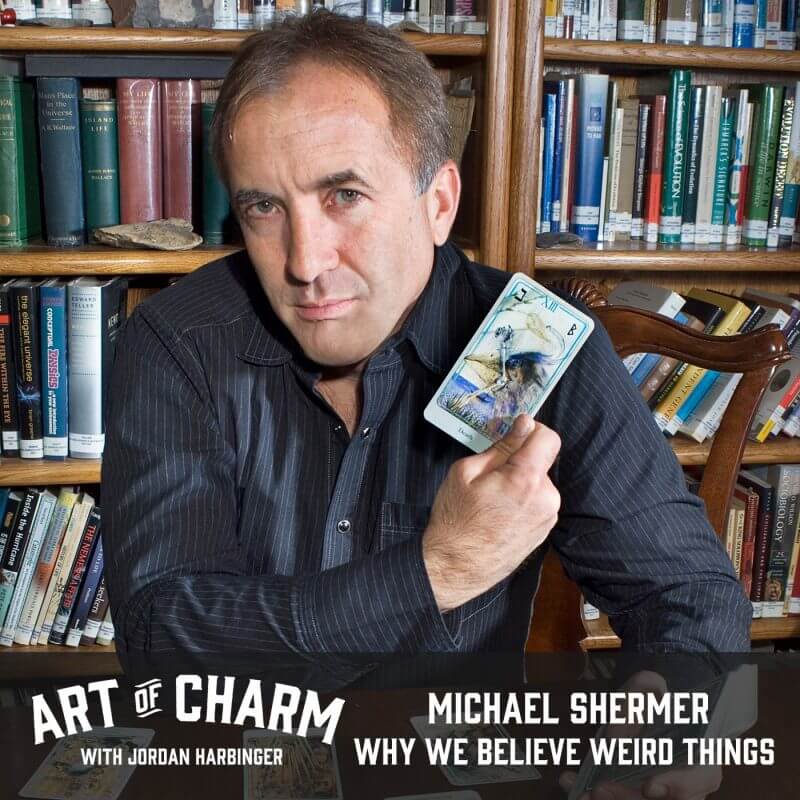

Michael Shermer (@michaelshermer) is the founder of Skeptic magazine and several books on the nature of belief. He’s the Director of The Skeptics Society, a non-profit dedicated to the promotion of science, reason, and critical thinking. He joins us to discuss why people believe weird things.

The Cheat Sheet:

- How do beliefs form in our brains and persist even when we know they’re wrong?

- Why do skeptics (and restaurant owners) scowl at the mention of Uri Geller?

- Why are smart people even more susceptible to faulty beliefs?

- How do our genes influence our political and religious beliefs?

- What’s the difference between a skeptic and a cynic?

- And so much more…

[aoc-subscribe]

Chances are pretty good that you believe — or have believed at some point in your life — something that you can’t really explain logically. Whether it’s faith in a particular religion, certainty in a series of conspiracy theories, or unquestioning adherence to a political party, we’re all susceptible to blind belief in something — no matter how smart we think we are.

Michael Shermer, founder of Skeptic magazine, Director of The Skeptics Society, and most recently the author of The Moral Arc: How Science Makes Us Better People joins us to examine why we’re hard-wired to believe weird things and how we can use science and develop the critical thinking skills to question everything skeptically without succumbing to cynicism.

More About This Show

Skeptic magazine founder Michael Shermer knows that people hear the word “skeptic” and automatically think of curmudgeonly naysayers who shoot down the existence of anything in which they don’t believe. But he makes it clear there’s a difference between being a curious, open-minded skeptic and a stubborn, closed-minded cynic.

“Skepticism is not a position you just automatically take on all claims a priori. It depends on the evidence of each particular claim. Think of it as the Null hypothesis in science. Your claim is not true until you prove otherwise. And once you’ve provided evidence, then we reject the Null hypothesis and assume that your idea could very well be true. And that’s how we treat all claims. It’s not that there can’t be a Bigfoot; you say ‘I believe in Bigfoot,’ and I say, ‘That’s nice, but show me the body.’ We just have to have the evidence for it.

“Same thing with aliens. They might be out there. They might have come here. We just need to see the evidence for it before we decide definitively what we are to believe in it…it’s just the scientific way of thinking.”

While Michael wasn’t raised in any particular faith, he converted to Christianity as a high school senior and, a few years later, renounced his belief in God entirely — which is perhaps a testament to his open-minded approach and close examination of everything he doesn’t fully understand. During his college years, his interest in science led him to study the wave of paranormal and pseudoscience that was gaining popularity in the ’70s.

That wave was responsible for influencing a lot of fledgling skeptics — Michael included. It was personified at the time by famous “spoonbender” Uri Geller, who claimed to manipulate mind over matter — mainly defenseless silverware — with his psychic powers. The media and public marveled at Geller’s ability to seemingly provide evidence of these powers under scientific scrutiny — until skeptics like James Randi and Ray Hyman figured out Geller’s parlor trick and recreated it under similar scrutiny.

But even being thoroughly debunked didn’t stop mining companies from paying Geller top dollar to find minerals with his “psychic” powers in the ’80s. In fact, he still enjoys wealth and celebrity after decades of insisting his displays of psychokinesis, dowsing, and telepathy are genuine — although “he’s pretty much admitted that it was a magic trick,” says Michael, “but not quite. He hasn’t come out fully and said ‘I was scamming people.’ He just kind of does the wink, wink ‘We all know what I was doing’ sort of routine with magicians now.”

It plays into the confirmation bias — or what Michael calls “motivated reasoning” — with which humans are hard-wired. “We’re motivated to reason our way to finding what we want to be true…to be true,” says Michael.

Even scientists aren’t immune to this line of reasoning, but observing the protocols of science keep their observations honest to overcome whatever biases they may have or outcomes they may predict.

“Maybe you have a bias against psychic power and it really exists — and you’re missing it. That would not be good, either!” Michael says. “We have to do it fair because we know the human brain is not unbiased. It definitely filters data in a way that can contaminate our conclusions. The entire scientific process for centuries has been refined to work around the psychological cognitive biases that exist.”

Listen to this episode of The Art of Charm in its entirety to learn more about confirmation bias as motivated reasoning, how Michael Shermer was able to debunk so-called psychic medium John Edward in a few sentences (and why Edward is still touring among his true believers in spite of this), how cold reading works, why we gravitate toward news and entertainment that reinforces the beliefs we already have, the difference between profiling and running the data, how sensory data creates beliefs, why we believe first and seek confirmation for our beliefs later, how evolution has led to moral tribes, the genetics behind personality temperament, why we get a rush of dopamine when we come across information confirming what we already believe, how different political groups can view the world so differently, why people double down on their faulty beliefs, and lots more.

THANKS, MICHAEL SHERMER!

Resources from this episode:

- Skeptic

- The Moral Arc: How Science Makes Us Better People by Michael Shermer

- Skeptic: Viewing the World with a Rational Eye by Michael Shermer

- Other books by Michael Shermer

- Michael Shermer’s TED Talks

- Michael Shermer at Twitter

- Penn & Teller’s Showtime page

- James Randi exposes Uri Geller and Peter Popoff (video)

- Michael Shermer Debunks James Van Praagh & Psychics (video)

- The Full Facts Book Of Cold Reading by Ian Rowland

You’ll also like:

- The Art of Charm Challenge (click here or text 38470 in the US)

- The Art of Charm Bootcamps

- Best of The Art of Charm Podcast

- The Art of Charm Toolbox

- The Art of Charm Toolbox for Women

On your phone? Click here to write us a well-deserved iTunes review and help us outrank the riffraff!