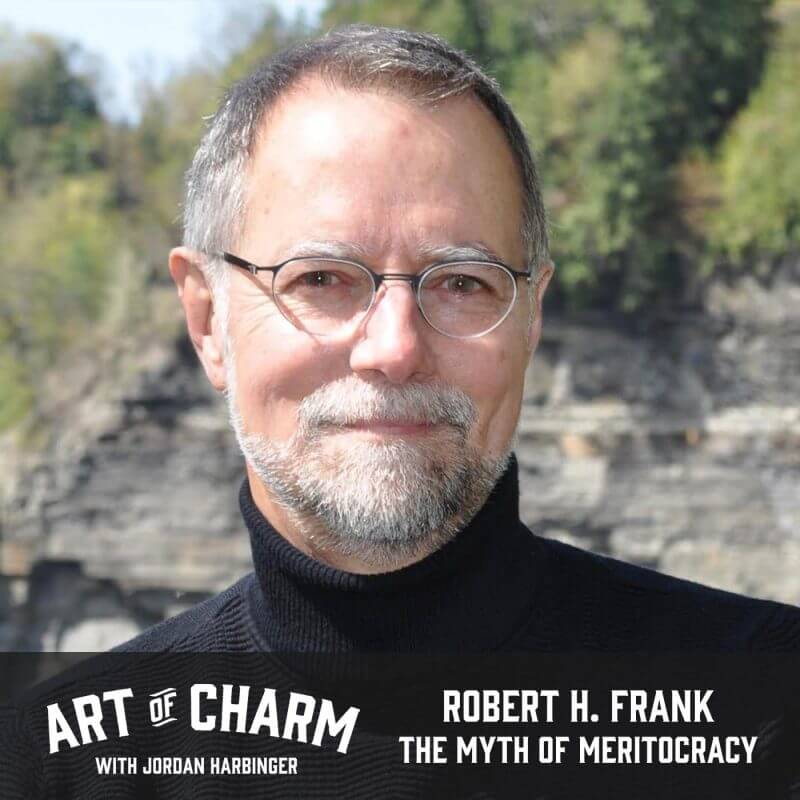

Robert H. Frank (@econnaturalist) is the HJ Louis Professor of Economics at Cornell University and author of Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy.

“I am a great believer in luck. The harder I work, the more of it I seem to have.” -Coleman Cox

The Cheat Sheet:

- As we strive to achieve success, there are natural limits on how hard we can work and how smart we can be. There’s no denying that luck plays a part in this achievement.

- Understand the role of luck, talent, and hard work in the overall formula.

- Discover why we tend to minimize the role of luck in our success.

- Find out how to maximize our luck in life by way of context outside of talent and work.

- Learn new ways to look at the luck factor and turn it to our advantage.

- And so much more…

[aoc-subscribe]

If you’re listening to this show right now on your smartphone that you bought with your credit card in a western country and you’re thinking, “Gee, I just can’t catch a break,” the truth is you have caught many breaks — possibly by birthright — just to find yourself where you are right now. And as random as such breaks might seem, you probably can’t help but wonder if there’s a way to maximize your proximity to their fickle visitations.

Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy author Robert H. Frank joins us to talk about the part luck plays in anyone’s success story — a quality seriously underrated or overrated depending on who’s telling that story — and how we can better increase the chances it will smile on us. Listen, learn, and enjoy!

More About This Show

You can’t make plans around good luck, yet the influence of happenstance in our daily lives is hard to deny. Perhaps few know this as well as Robert H. Frank, author of Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy.

After a second set of tennis with his friend one morning back in 2007, Robert complained of feeling nauseous. Moments later he collapsed, motionless, without any discernable pulse. It was later determined that Robert had suffered from sudden cardiac death, an episode from which only two percent of its victims survive. But he was lucky.

“The fact that I made it was attributable to an extraordinarily low-odds event,” says Robert. “Before I had collapsed on the court, there had been two auto accidents that occurred near the tennis center. Ambulances had been dispatched from town, which was five or six miles away — normally it would take thirty to forty minutes to get an ambulance to a site out in the country.

“One of the accidents wasn’t serious, and so when the call came in that they had a serious case at the tennis center, the driver of that second ambulance was able to peel off, come to my aid only a few hundred yards from where he was, and, except for that immediate attention, I would be among the ninety-eight percent of the people who don’t survive episodes of cardiac death.”

As an economist, it’s not in Robert’s nature to say he was destined to survive. But lucky? He’ll take it. Obviously, not suffering from cardiac arrest would have been luckier, but he happened to be in the right place at the right time that its effects were mitigated and he lives on to write books and appear on podcasts.

But being in the wrong place at the wrong time can just as easily result in consequences beyond anyone’s control, such as when founding ELO member Mike Edwards was killed by an errant hay bale in a freak crash in 2010.

As a society, we don’t shy away from saying luck (or lack thereof) had a part to play in each of these scenarios. It’s when life and death aren’t on the line that we seem to easily dismiss its influence.

“When luck plays out as it normally does in life, it’s in far more subtle ways and we tend not to notice it’s important in those cases. We see successful people, thirty years into their careers; almost all of them are hard-working and talented. There are a few examples to the contrary — lip-syncing boy bands or various others who have succeeded without much hard work or talent — but most of the people who make it big really do work hard. They really are talented.”

As someone who’s experienced success constructs a narrative of the path he or she has taken to get there, it’s the bumps along that path that tend to be most memorable: the long hours, the solved problems, and the formidable opponents easily spring to mind because those are the hurdles encountered most often on such a path. But easily forgotten are the infrequent — but not inconsequential — boosts that also happened. We might forget the teacher who kept us out of trouble in the eleventh grade. Or the promotion we got when a slightly more qualified colleague couldn’t accept it because he had to care for an ailing parent.

“So you’re riding a bike into a heavy wind; you’re conscious of that wind and how it’s making life difficult for you every inch of the way,” says Robert. “The course changes direction; now you’ve got the wind at your back. You’re delighted to have gotten out of that headwind and you’re happy for — what? Twenty seconds? And then after that, it’s no longer in your conscious focus. You’ve got a wind at your back, but you’re not thinking about that because there’s nothing you have to do. You don’t have to work against it.

“And it’s the same with events in life. If you had to battle against an obstacle, you’re hyper-conscious of that. You remember it; you include it in your story. If you had a wind at your back, that’s something you just don’t notice. And so I think in complete innocence, successful people tend to look back on their lives and say, ‘Wow. I did it all myself.'”

Or, as E.B. White once said (and Robert is fond enough of quoting that he paid $500 for the rights to include it in his book), “Luck is not a subject you can mention in the presence of self-made men.”

Listen to this episode of The Art of Charm in its entirety to learn more about the availability heuristic, how one might gently raise the subject of luck around a successful person without being kicked out of the mansion top hat lobster party (e.g., avoid using the phrase “you didn’t build that”), the consequences of bad decisions for people with money vs. people without money, how even the most talented and hardest working can be undone by somebody with a certain amount of luck, how technology has increased the role of luck, how the month of your birth influences your luck (it has nothing to do with the zodiac), how we can be more open to receiving the good luck that comes our way, how even bad luck can serve us, and lots more.

THANKS, ROBERT H. FRANK!

If you enjoyed this session with Robert H. Frank, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Robert H. Frank at Twitter!

Resources from This Episode:

- Transcript for Robert H. Frank | The Myth of Meritocracy (Episode 599)

- Success and Luck: Good Fortune and the Myth of Meritocracy by Robert H. Frank

- Why Luck Matters More Than You Might Think by Robert H. Frank, The Atlantic

- Robert H. Frank’s website

- Robert H. Frank at Twitter

- “You didn’t build that.”

- John Locke’s Labor theory of property.

- Outliers: The Story of Success by Malcolm Gladwell

- Is Justin Timberlake a Product of Cumulative Advantage? by Duncan J. Watts, The New York Times Magazine

You’ll Also Like:

- The Art of Charm Challenge (click here or text 38470 in the US)

- The Art of Charm Bootcamps

- Best of The Art of Charm Podcast

- The Art of Charm Toolbox

- The Art of Charm Toolbox for Women

- Find out more about the team who makes The Art of Charm podcast here!

On your phone? Click here to write us a well-deserved iTunes review and help us outrank the riffraff!