Stop worrying so much about where your inspiration is coming from and just create.

“People think that authors are writing exactly what they know, but I think a lot of times, authors are writing what they’re trying to figure out.” -Austin Kleon

The Cheat Sheet:

- Are you more proud of the things you’re doing today than the things you were doing a year ago? (04:52)

- Is any creative work truly original? (06:40)

- Most of your favorite artists are shameless thieves — and will freely admit it. (09:37)

- What’s the difference between being legitimately influenced by someone and ripping them off? (12:52)

- The Elevator Test is a simple ethical gut check that can help clarify whether you’re invoking fair use or just being a plagiarist. (18:16)

- And so much more…

[aoc-subscribe]

The biggest hurdle to creativity is when people think they have to be original. If you accept that nothing is completely original and all creative work builds on what came before, it frees you up to start embracing influence instead of running away from it.

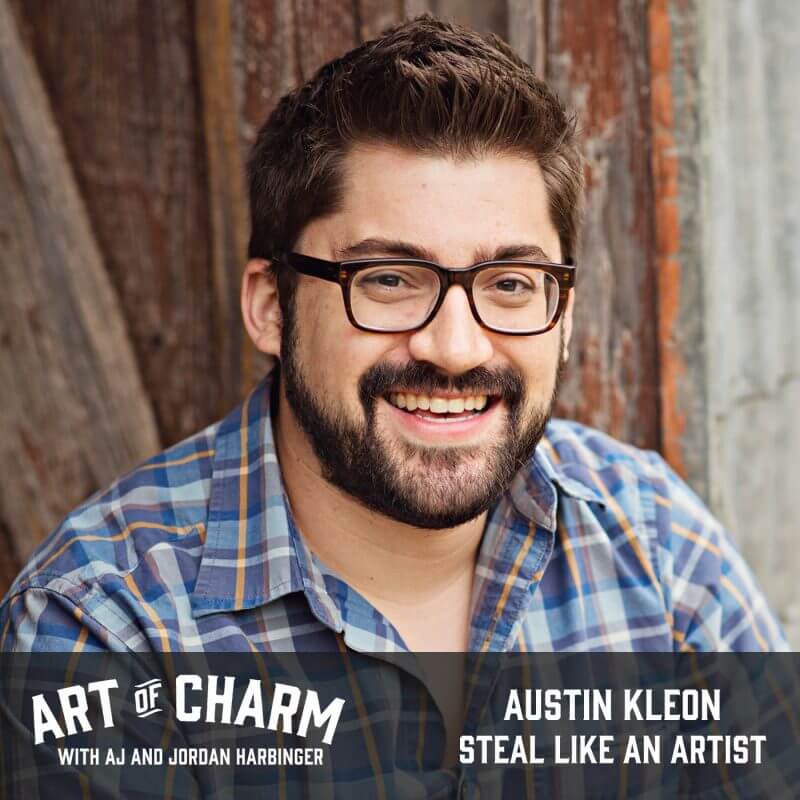

In episode 447 of The Art of Charm, we talk to Austin Kleon, the New York Times bestselling author of Steal Like an Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative (and its new companion, The Steal Like an Artist Journal: A Notebook for Creative Kleptomaniacs) about his unique approach to creativity in the 21st century. You’ll be motivated to stop worrying so much about where your inspiration is coming from and just create.

More About This Show

What do you say when someone asks you what you do? Austin Kleon is simply, as he says, “a writer who draws.” Sometimes he makes books with pictures; sometimes he makes art out of words. Either way, he’s always creating in ways that lead him toward self-discovery.

While a reader may be under the impression that authors are writing books about things they know, Austin says that they’re really writing about what they’re trying to figure out, and he’s no exception.

But authors aren’t (and shouldn’t be) the only ones who aim for self-discovery through their work — even if it’s an awkward process. He points out something that Alain de Botton once said: “Anyone who isn’t embarrassed by who they were last year probably isn’t learning enough.”

While it’s true that going over past work may elicit the dreaded cringe factor, it’s a helpful step toward getting better. Take cues from this sometimes painful process to learn and improve rather than letting it hold you back from evolving.

Sometimes, though, we cringe at work we do for reasons that aren’t really in our control. Take the elusive idea of “originality,” for instance. No matter what it is we do, the drive to create something that’s never existed before can be overpowering. If we fail in this — in our own eyes or of those who critique or judge our work — we may even skip cringing and slump right into shame mode.

But the reality is, after thousands upon thousands of years of human history, the likelihood of truly creating something entirely new out of the space between thin air and genius is slim. We’re influenced by what’s come before, and we independently arrive at conclusions that have almost certainly crossed the minds of at least a few among the billions of others who have walked the planet.

We really should be kinder to ourselves.

Overcoming the Myth of Originality

“Creativity is so mythologized and it’s so mystified,” says Austin. “But really, for me, creativity is just a tool. It’s just something that we all have access to. And for me, my definition of creativity is just taking what’s in front of you and everybody else and just rearranging it into a new solution.”

The biggest problem faced by people who aspire to create is when our culture’s emphasis on originality paralyzes them before they can even begin. These people may even take drastic measures to avoid being influenced by existing work in an effort to create something purely from themselves. But few — if any — masterpieces arrive from the ether.

“You look at the people in our culture who are doing amazing work,” says Austin, “and very few of them actually come up with these ideas out of nowhere — and it’s true in any form. You’ve got someone like Kobe Bryant who talks about his basketball moves and the way that he learned was he sat in front of the VCR and he memorized these moves. And then he went on the court and he tried them out. The thing is, he didn’t have the same body type as some of the guys that he was copying, so he had to kind of transform the move into something of his own.”

“You’ve got someone like [Quentin] Tarantino, who’s one of our greatest filmmakers, and pretty much all of his movies are just…each scene is like an homage to another movie, but then it makes this whole that’s just Tarantino, right?”

Most of your favorite artists are shameless thieves, and will freely admit it. In other words, they don’t get bogged down by the fear of not creating something entirely from themselves — they observe what’s come before, learn from these influences, and adapt the work to suit their needs.

Copyright and Fair Use Concerns

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time you want to design a car. But where do you draw the line when it comes to being influenced by something that someone else has done and avoid ripping it off to the point of plagiarism?

“When it comes to making your own work, I really think it’s all about the transformation,” says Austin. “It’s all about…are you taking other people’s ideas and are you doing something new with them? Are you rearranging them in some way that adds value to them — that adds value in the wider culture?”

“So if you’re scraping someone’s article and reposting it on your blog without credit, that’s crappy stealing. But if you’re taking their article that they wrote and you’re adding your own two cents and then you’re adding a half dozen other voices that you’ve cobbled together into a new piece, then that is something new.”

One way that this cobbling occurs is by invoking fair use — when copyrighted material is legally modified in a way that doesn’t require permission from the copyright holders. Austin gives an example from his own work in the form of newspaper blackout poems:

“What I do is I take an article from the newspaper,” says Austin. “I put a box around a few of the words until it makes kind of a funny phrase or a mini haiku, almost. And then I black out the rest of the article so it almost looks like if the CIA did haiku.”

As fodder for these projects, Austin uses the New York Times — which, appropriately enough, asked him to write a piece about fair use.

“What I’m doing with the poems is I’m transforming a piece of journalism into a piece of poetry,” says Austin. “So right there in that transformation, I’m not taking any kind of intellectual or financial thing away from them. I’m just making this new thing. so there’s a transformation there. There’s also a thing in fair use about how much you take from the thing you’re stealing from. I only take, maybe, 15-20 words out of a 500-word article.”

In a scenario like this, not only is the artist getting something out of the process, but the content originator benefits in other ways, as well.

“The New York Times is not losing any business because I’m making poems out of their newspaper. If anything, I’m giving value to their newspaper because I’m having people actually think about the paper as something that you interact with and something that you actually open up and look at and can make things out of, and there’s actually been some newspapers who have run their own newspaper blackout poetry contests because they realize, ‘Hey, if we run this contest, people will have to buy a newspaper to make a blackout poem out of it!'”

The Elevator Test

Whenever Austin has doubts about whether he’s crossed a fair use line or not, he gives himself an ethical gut check by way of this Elevator Test:

“If I was in a stuck elevator with the person I’m stealing from,” he ponders, “what would they do? Would they give me a little pat on the shoulder and say, ‘Hey, man! You know, I saw that. That was a really good way you took that and ran with it,’ or would they punch [me] in the face?”

And this raises a fair point. If you were to find that your work was being similarly appropriated, how would you feel about it? One way of looking at it: if you’re creating something that someone else adapts for their own purposes, it must mean you’re creating something worthwhile. As long as this fair use comes with fair credit and they actually acknowledge you as a source, you can use it to your advantage.

(For the record, if you want to fairly use anything you find in these Art of Charm podcasts, please feel free — just make sure to credit us and let us know about it!)

Playing Well with Others: The Synergy of ‘Scenius’

Going it alone is one way to create, but there’s a lot to be said for the synergy of teamwork.

“Sharing is really how people grow and develop. Being part of a group of people who are sharing ideas and copying from each other and stealing from each other, I mean, that’s how some of our greatest art kind of came about. There’s an idea; we think of creativity as being the domain of the lone genius, right? This super-humanly talented, gifted person.”

“But there’s kind of a flip side of that and it’s something that the musician Brian Eno calls ‘scenius.’ And what scenius is is it’s the communal form of genius. It’s actually a whole network of people — a scene — in which these special geniuses kind of work on their craft and they come up with their ideas and they kind of rise out of it.”

“Like a great example, since we were talking about music before, is someone like Bob Dylan. Bob Dylan starts out; he’s just this kid from Hibbing, Minnesota, and he travels around a little bit and he ends up in the very rich folk scene of Greenwich Village. And he learns all kinds of songs off of these other folk singers and he’s running into all these different kinds of people and the whole scene at the time. Dave Van Ronk, who the Cohen Brothers made that movie [Inside Llewyn Davis] kind of based on his life…Dave Van Ronk said, ‘We were all stealing from each other. Everybody was lifting arrangements and all these old songs off each other; Dylan just happened to be the most successful at it.'”

In Show Your Work, Austin tells us how to join a rich, creative scene and become a scenius. “Share your stuff. Share your ideas. Share the albums you’re listening to. Share chords. Share songs that you’ve learned. That is how you become a valuable part of one of these networks. And then the network pays you back by making you a member and everyone else is sharing their own stuff.”

Nowadays, Austin points out, the Internet allows individuals to share and influence on a global scale, so becoming a scenius may not be as out of reach as it might seem to someone living in a town where the population of livestock outnumbers the population of people.

“You take someone like my friend Maria Popova,” says Austin, “who runs Brain Pickings. She’s a blogger and what she does is she shares mostly what she reads. And she calls herself a curator, but I see her as…she’s just a blogger. She’s a sharer of ideas. But what she does that’s so valuable for everyone is she’s created this gigantic repository of stuff that she’s read and come across and she’s become a very valuable part of this kind of online scenius and this whole…little empire just from sharing. That’s the kind of world that we’re living in right now.”

THANKS, AUSTIN KLEON!

Resources from this episode:

Steal Like An Artist by Austin Kleon

The Steal Like an Artist Journal by Austin Kleon

Show Your Work by Austin Kleon

Newspaper Blackout by Austin Kleon

Austin Kleon’s weekly newsletter

Austin Kleon at TEDxKC

Sick in the Head by Judd Apatow

The Art of Charm bootcamps

You’ll also like:

-The Art of Charm Toolbox

-Best of The Art of Charm Podcast

On your phone? Click here to write us a well-deserved iTunes review and help us outrank the riffraff!