Technology can save you a lot of time — when it’s not helping you waste it. Break tech addiction by learning how it gets you hooked in the first place.

“I need to use what I know about human behavior and consumer psychology to put technology in its place.” -Nir Eyal

The Cheat Sheet:

- Does technology work for you, or are you working for technology?

- Learn how and why habit-forming devices and apps are developed.

- What are the triggers in your life?

- Discover how variable rewards train you like some kind of nervously pecking lab pigeon.

- How can you prevent “investing” in bad habits?

- And so much more…

[aoc-subscribe]

Ever find yourself promising that you’ll go to bed just as soon as you answer one more email? Maybe after one more status update on Facebook? Or after you retweet this clever thing your best friend passed along from his favorite celebrity’s second cousin? And even though your eyes are red and watering, you can’t tear them away from that ludicrously colorful game with the catchy ditty until you hit the next level. How did it get to be 4 a.m. and why did your wife leave you a pillow and blanket on the couch?

Technology’s got you hooked, and more often than not, it’s by very careful design. Nir Eyal can tell you all about it in his book Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products (but he can also tell you how to break away from these habits). Join us in episode 431 of The Art of Charm, where we talk about this curious intersection of psychology, technology, and business that most (if not all) of us have experienced in this modern age of perpetual distraction.

More About This Show

What makes products like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, and Slack so, as consumer psychology expert Nir Eyal puts it, sticky? That is, what makes it nearly impossible for you to set your phone down or walk away from your computer at the expense of other things you could and should be doing?

Nir spent a lot of time in the gaming and advertising industries to find out, and his research went into Hooked as a way to put these techniques to better use.

“There’s no reason that all this consumer psychology needs to be pent up into just gaming and advertising — those industries that are dependent on mind control,” says Nir. “I thought…all sorts of businesses can create healthy habits — and users can improve people’s lives — [by using] the same techniques.”

One example he cites (and believes in so much he became an investor) is 7 Cups of Tea, a service that offers “free, anonymous, and confidential chat with trained volunteer listeners.” Essentially, it helps people who might otherwise go to therapists but can’t afford to — from veterans returning with PTSD to depressed teens to parents of children with disabilities — talk about their problems without the cost or hassle.

“The kicker is that once they form this habit of being listened to, users [are taught] how to listen themselves, and that’s what actually turns out [to] make them better,” says Nir. If you can be trained as someone who can provide help to someone else through this service, you actually get better…they use these hooks for good.”

Now that we understand Nir’s angle in taking the blueprints of manipulation from companies with less noble intentions and handing them over to others that are trying to make a positive difference in people’s lives, we can let him deconstruct the process for us so we can more easily turn away from it.

The Struggle is Real

Even Nir falls prey to the attention divide, and he knows how the strings are pulled. “I’ll be the first to admit — I’m baring my soul here — I struggle,” he says. “This is the struggle for me even though I know the psychology…I haven’t beat this! This is a constant struggle and guess what? It’s not going to get easier. Technology is getting better and better. Look at what’s coming out. We’ve got virtual reality, we’ve got augmented reality, we’ve got better devices, we’ve got the Apple Watch; these things are going to change our habits…[they’ll] give us a lot of benefits, but we also need to be on guard.”

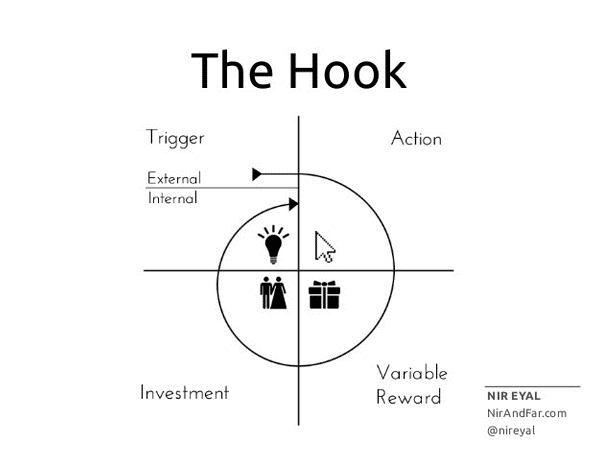

On guard against what? The stimuli that encourage us to integrate a new pattern of behavior — a habit (that is, a behavior done with little or no conscious thought) — into our current routine. There are four fundamental steps that lead to the forming of a habit: trigger, action, variable reward, and investment; this is what Nir calls the Hook Model.

The Hook Model

From the perspective of a company that’s trying to get you to use its product or services, the hook is an experience designed to connect your problem to the company’s solution. Here’s how it happens, and how Nir suggests you can put a halt to it (if you so desire).

Trigger

The trigger — the part that grabs your attention in the first place — can be internal or external.

An external trigger is designed in such a way that the information for proceeding to the next layer of the hook is built into it. Think of a button on a website that invites you to “buy now” or an icon you can click right now to tweet about something.

An internal trigger is designed to use an association that you’ve already developed — like an emotion, a situation, a routine, or even a person or place — to prompt you to the hook’s next layer. For instance, when you’re lonely, you might be inclined to go browse and interact with Facebook. When you’re bored, you can go watch videos on YouTube. Uncertainty about something may have once been a trigger for asking questions of real-life people, but now you know you can just go “Google it.”

Nir suggests a few ways to remove some of our more common triggers:

Leave the phone out of the bedroom. “Two thirds of Americans sleep with their phones right next to them,” says Nir, “and I think that’s a mistake. If you want to get better sleep, if you want to have more nookie with your significant other, leave the phone out of the bedroom!”

Adopt a strict “no Internet policy” between certain times. In Nir’s household, this works in tandem with leaving the phone out of the bedroom.

When you’re on the Internet, use an ad blocker. This won’t sit well with a lot of people who rely on ad revenue for their business model, but from a would-be consumer’s standpoint, it makes sense. “Why would you want to see ads?” wonders Nir. “These are just triggers.”

Disable notifications.

Leave the phone out of the board room. Ever been to an office meeting and witnessed the boss or someone else in an “important” position pulling out their phone to check and respond to whatever critical email has been building up since they walked in the door 10 minutes ago? It’s not only keeping their attention away from whatever’s being discussed in the meeting, but it’s distracting everyone else in the room. Last but not least: it’s rude. Nir proposes something akin to the digital version of a hat rack. “Back in 1940s and 1950s, when you’d walk into a private space, you would put your hat on a hat rack,” says Nir, “and that signified that you [were] no longer in the public space; you’re in the private space.” He suggests something like a charging station for phones in the hall outside — away from arm’s reach and convenience-goaded temptation.

Action

When products are successfully designed to get us to form habits around them, they make the action of pursuing such a habit as easy as possible for us. Think of scrolling down the page on Pinterest or hitting the Play button on a YouTube video — these are very simple actions we do without really thinking.

Taking pause at this point to consider if an action is something we need to be doing or if it’s just a distraction can be a challenge. “There’s…almost this new burgeoning industry of technologies I call attention retention devices,” says Nir, “that help us focus [and] stay engaged with what we want to be doing” — basically just making it a little bit harder to perform an action that we’ve deemed non-critical.

Nir himself uses an app called Stayfocused, which blocks out certain sites at certain times of the day that the user has designated for other activities. For instance, Nir needs a couple of non-distracted hours in the morning to focus on his writing. “From 7:30 to 9:30 I can’t check email [or] Twitter,” says Nir. “Stayfocused blocks just those two sites and it’s made a world of difference.”

And remember how Nir suggested imposing a household Internet curfew between certain times of the day to remove the trigger that invites habitual online behavior? Remember, too, how he said even he’s not immune to temptations of the hook? He remedied this by going down to the hardware store and purchasing an outlet timer; it’s programmed to shut off his Internet router at 10 p.m. every night!

There are ways to get around these hindrances in case of emergency, of course, but they make the associated actions just a little more inconvenient to pull off — and that’s really the goal here.

Variable Rewards

In the 1930s, behaviorist and operant conditioning pioneer B. F. Skinner discovered that pigeons could be enticed to peck a disk in anticipation of a food pellet — a proper reward for a hungry pigeon. It turns out that this disk-pecking response occurred more frequently when variability in the rate of reward was introduced.

This principle works for humans, too, so don’t act so smug the next time you try to insult someone by calling them a bird brain.

“The brain is an amazing pattern-matching device,” says Nir. “So when we screw with the brain and something doesn’t occur in a predictable schedule, that causes us to increase focus [and] increase engagement…it’s highly habit-forming.”

He uses the slot machine, that famous Las Vegas casino staple, as an example. What makes slot machines fun? You put in a coin and pull the lever; you don’t know what’s going to come out — maybe nothing. But it’s the chance that something might come out that keeps you feeding it coins.

Even if gambling’s not your thing, you’ve probably got something equally appealing that exploits your brain’s search for a variable reward of some kind.

“What makes sports interesting,” says Nir, “what makes Twitter and Facebook and even the news [interesting] is the variability. What’s going to happen? The unknown mystery! That’s what we want! It’s the exact same thing that kept Skinner’s pigeons pecking.”

According to Nir, there are three types of variable rewards: rewards of the tribe, rewards of the hunt, and rewards of the self.

Rewards of the Tribe are things that feel good, have this element of variability, and come from other people: partnerships, cooperation, and competition — these are all variable rewards of the tribe.

Rewards of the Hunt are about the search for resources: information or things. (This is what keeps us pulling the lever on that slot machine or scrolling down the Twitter feed for something that catches our eye).

Rewards of the Self are all about the search for things that are intrinsically pleasurable. They don’t come from other people, and they’re not about material or information rewards. These are the things that feel good in and of themselves. For example, the search for mastery, consistency, competency, and control. The best online example is gameplay.

“When I play Candy Crush or Angry Birds, I’m not playing with other people.” says Nir. “I’m not even winning anything, but there’s something fun about getting to the next level…by the way, that’s exactly what makes us keep checking email over and over and over again — the sense of mastery and completion and competency and control for finishing that unread message” and getting to the fabled inbox zero.

If you find yourself wasting too much time in this phase of the hook, you can try delaying the reward.

“I’ll go online and I’ll see an article that looks interesting and I’ll start reading it — just this one article,” says Nir. “Then over here in the masthead there’s this other article that looks cool, and another…article that looks interesting.”

Suddenly, something that should have only taken five minutes balloons into hours. Nir found this happening over and over again, so he established a rule that he would no longer read articles online. Instead, he uses an app called Pocket that saves articles for later (in conjunction with another app called Lisgo, which then reads them to him).

This leads into another tactic Nir employs that he calls temptation bundling. “If you can take something you don’t like doing and…pair it with something you do like doing, you’re more likely do the thing you don’t like doing,” says Nir. So he saves up those articles he wants to read with the Pocket app and lets the Lisgo app read them to him only when he’s exercising or walking.

Investment

This is where the user puts something into the product in anticipation of a future benefit, and it loads the next trigger. “When I send someone a message on WhatsApp, there’s no immediate gratification; I don’t get anything,” says Nir. “No points or badges, but when I take the time to invest in that platform and send a message, I will be prompted back with a notification that says, ‘hey your friend just replied!’ That reply is an example of an external trigger that brings me back to the hook once again.

So how do you make sure you don’t invest? “One thing that I see happening with a lot of companies is that they play this email ping-pong,” says Nir. “You get an email [and] you feel like you’re obliged to reply — not only do you reply, but you reply right away!”

Instead of sending the email right away, you can use a tool like Boomerang. It allows you to send something — which gets it out of your inbox — but it delays the time that it’s received by the person on the other end. In this way, you can batch your emails and know they won’t be responded to immediately (which would just fill up your inbox yet again).

The Take Away

“The gambling industry already knows these tactics,” says Nir. “The gaming industry knows how these things work, so they don’t really need my help.” Nir wrote Hooked as a manual for the makers of products and services that genuinely strive to benefit people but don’t get the attention they deserve because they don’t know these tactics.

Armed with the secrets we talk about in this episode of The Art of Charm, you should understand the basics of building hooks into your own business model as well as know how to resist it when you discover such hooks being used on you. Listen and enjoy!

THANKS, NIR EYAL!

Resources from this episode:

Nir and Far: A Blog About Behavior Engineering

Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products by Nir Eyal

7 Cups of Tea

Life360

Pocket

Lisgo

Boomerang

The Art of Charm bootcamps

You’ll also like:

-The Art of Charm Toolbox

-Best of The Art of Charm Podcast

On your phone? Click here to write us a well-deserved iTunes review and help us outrank the riffraff!