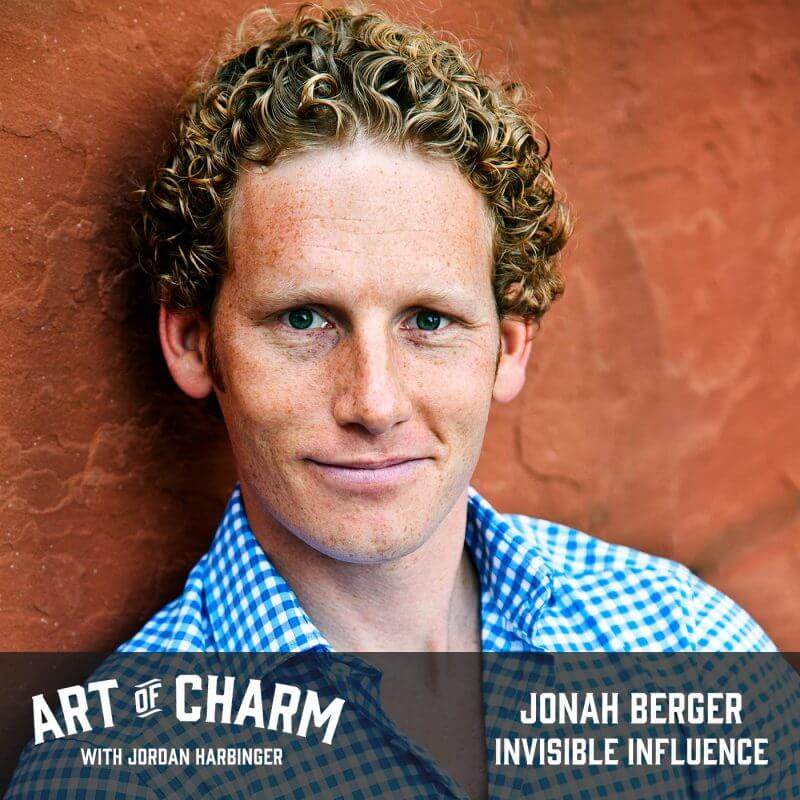

Jonah Berger (@j1berger) has spent over 15 years studying how social influence works and how it drives products and ideas to catch on. He’s a marketing professor and author; his new book is Invisible Influence: The Hidden Forces that Shape Behavior.

The Cheat Sheet:

- We like to believe we’re so special that our choices are driven by personal preferences and opinions; the fact of the matter: other people have an influence over almost everything we do.

- Rather than seeing influence as negative and manipulative, we should understand how to use it as a toolkit for making better decisions.

- Sometimes we allow our social groups or cultural upbringing to influence us toward underachievement.

- Learn the one trick that allows negotiators to be five times more successful.

- How do we protect ourselves from undesired influence?

- And so much more…

[aoc-subscribe]

Whether we realize it or not, other people have a surprising impact on almost everything we do. It can be hard to recognize this influence in our own lives, but just because we can’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not there. By better understanding how social influence works, we can harness its power to motivate ourselves and others, be more influential, and make better decisions.

Jonah Berger, marketing professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and author of Invisible Influence: The Hidden Forces that Shape Behavior, joins us for episode 529 of The Art of Charm to peer into the unseen clockwork of this influence and figure out how it operates.

More About This Show

“I think whether we’re a leader of a big company, a manager of a small business or just an individual within an organization — or even in our personal lives — influence is a powerful toolkit we can use to help make better decisions, help shape companies, and make ourselves more successful. It’s a toolkit that everyone needs to use and understand,” says Jonah Berger, author of Invisible Influence: The Hidden Forces that Shape Behavior.

While it may seem like our choices are driven by our own personal preferences and opinions, the influence of others makes a mark on everything we do — whether we wish to admit it or not. We may believe our actions are completely independent and going against the flow of what everyone else is doing, but the reality is that our decisions are largely dependent on the influence of others — whether we conform to them or make an effort to act counter to them.

“In American culture, influence is a bad word,” says Jonah. You say influence, people think manipulation. [As] Americans, we love to see ourselves as independent, special, unique snowflakes that are so different from everybody else — particularly the millennials. Their parents raised them to say ‘We’re different than them and everybody!’ If difference is good, then we don’t want to think that we’re influenced — that we’re the same. We don’t want to think that others are affecting us.”

Research suggests that, even when influence is good, people still don’t think they’re susceptible to it. It’s not just about self-presentation — we simply don’t see it because it often happens unconsciously and below our awareness. Take, for example, the conventions of naming a baby. If asked, a parent-to-be will count relatives or old friends as being inspirational in the choice, but historical data suggests that similar names rise and fall in popularity based on the influence of others (and sometimes even events — like the weather).

“You’d think hurricanes would hurt the popularity of names,” says Jonah. “Hurricane Katrina, for example, should [have] decreased the number of babies born with [the name] Katrina — and they may have. But if you look at other K names? Well, 10% more babies were born with K names the year after Hurricane Katrina. Because people heard that K name a lot. Katrina made K names sound more familiar, and so [parents] were more likely to pick those names even though they thought it was their own preferences that were driving their choices.”

The Influence of the Subliminal

We’ve all heard the story about how movie theaters used to secretly mix frames of refreshing drinks and delicious popcorn into films being shown that would subliminally influence their clientele to spend money on concessions. While this particular example turned out to be an urban legend, it appears we’re influenced in ways that — on examination — act just as subtly to modify our behavior.

“We did a bunch of research a few years ago showing that if you voted at a school, you’re more likely to support a school funding initiative,” says Jonah. “Why? Well, you see school-related things. You’re in a school-related building. It makes you feel — even non-consciously — like you should support this initiative. Voting in a church, for example, might change how we vote on gay marriage or stem cell initiatives. These subtle things in our environment often affect us, even without us realizing it.”

The Influence of Society

Choices we make are further influenced by the social groups in which we find ourselves. For instance: firefighters, with an attitude nurtured by the importance of teamwork, tend to positively react when a friend happens to buy the same car they have — it’s a further point of bonding. A banker, on the other hand, might find themselves angry when a colleague does the same.

“It really depends on how we’re raised,” says Jonah. “It’s not that one thing is right or wrong; it depends on the environment that supports us.”

The Influence of Ethnicity

In academic scenarios, studies have shown that minorities will often perform below their aptitude because they don’t want to be seen by their peers as trying to act white. “Obviously, there’s no reason that academic success is a white thing,” says Jonah. “Everyone should and can do well in school. But the stereotype — this notion that trying hard in school is a signal of being white is really detrimental. It causes students to actually work less hard in school and do less well. And even skin tones — students that look more white, so let’s say Latino students, who have lighter skin — are more susceptible to this than Latino students who have darker skin, because they have outward markings already of being more a member of that group.”

In other words, we can be influenced to act against our own interests when we stand to lose face among our peers for stepping away from their established stance on something.

Listen to this episode of The Art of Charm to learn more about how our politics are influenced in ways that often seem counter to the overall message of a platform (e.g., so-called conservatives rallying against clean energy in spite of it being an alternative to reliance on foreign oil, better for national security, and more conducive to small government just because a highly visible liberal like Al Gore publicly stands for it), find out how producer Jason fares when faced with a live memory test meant to gauge susceptibility to influence, where we tend to meet our “soulmates,” how familiarity doesn’t necessarily breed contempt, the meaning of moderate similarity and optimal distinctiveness, hipsters on bicycles, signals of subcultural belonging, product placement as corporate sabotage, and lots more.

THANKS, JONAH BERGER!

Resources from this episode:

- Invisible Influence: The Hidden Forces that Shape Behavior by Jonah Berger

- Contagious: Why Things Catch On by Jonah Berger

- Jonah Berger’s website

- Jonah Berger at Twitter

You’ll also like:

- The Art of Charm Challenge (click here or text 38470 in the US)

- The Art of Charm Bootcamps

- Best of The Art of Charm Podcast

- The Art of Charm Toolbox

- The Art of Charm Toolbox for Women

On your phone? Click here to write us a well-deserved iTunes review and help us outrank the riffraff!