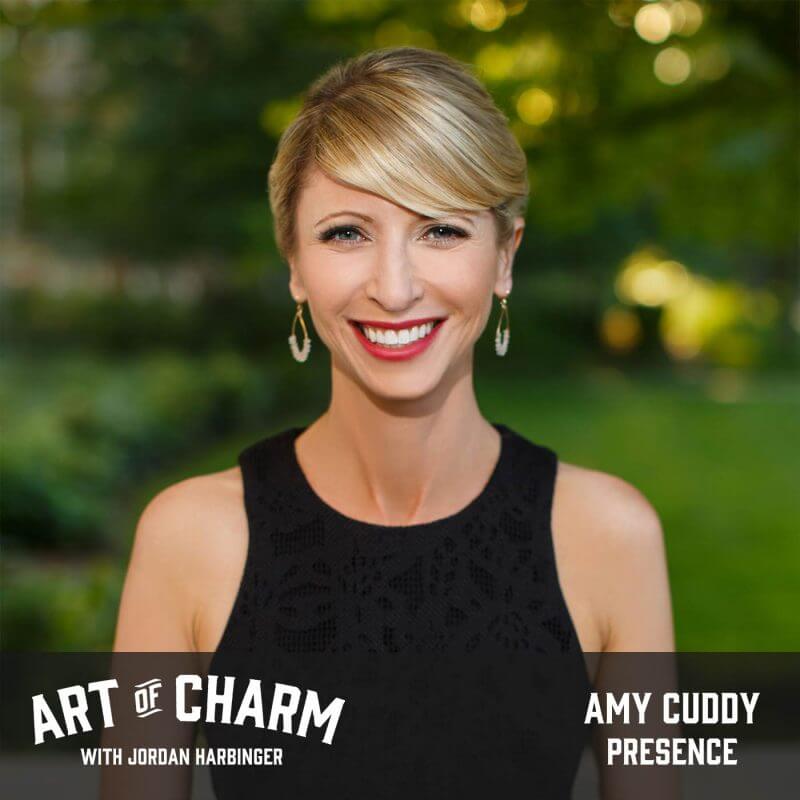

Amy Cuddy (@amyjccuddy) is a social psychologist, TED Talk speaker, and author of Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges.

The Cheat Sheet:

- What is presence, and why do the charismatic seem to have it in abundance while so many of us struggle to find it regularly in ourselves?

- Presence is a renewable resource — not a permanent state.

- Confident body language begets confidence and presence.

- Arrogance isn’t a proxy for confidence — why inauthenticity undermines trust, how you can keep yourself from conveying it, and how to spot it in someone else.

- Extroverts don’t have an unfair advantage when it comes to commanding presence; by the same token, introverts aren’t at a disadvantage.

- And so much more…

[aoc-subscribe]

When we try to fake confidence or enthusiasm, other people can tell that something is off, even if they can’t precisely articulate what that thing is. This is why we constantly stress the value of authenticity here at The Art of Charm.

But what is authenticity? It’s a word that’s used so often and in so many ways — along with mindfulness — that, if pressed, the average person might not even be able to define it. In this episode of AoC, we better clarify authenticity and learn how to summon its powers on command with Amy Cuddy, author of Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges.

More About This Show

Authenticity. Mindfulness. Presence. These are words you probably hear all the time — perhaps so often that you just nod your head at their mention — without really thinking about what they mean. They’ve become fuzzy, catch-all buzzwords applied in any number of disparate domains — from coffee shops to networking seminars to yoga classes — to convey more of a feeling than impart any precise, applicable meaning.

In her book Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges, social psychologist Amy Cuddy seeks to sharpen the focus and help us apply the best version of ourselves to whatever the world throws our way.

When considering the idea of presence, for instance, you probably have a vague idea that it’s something effortlessly commanded by society’s most charismatic. It’s common to assume celebrities must have a secret, endless reservoir of the stuff somewhere that’s replenished by the power of being adored by the masses. The reality: presence is something to which we all have access. Think of it as a quality available on tap rather than as an ever-flowing fountain — contrary to appearances, nobody’s on all the time.

“Based on the psychological research, I think that presence — the ability to be attuned to and comfortably able to express the best parts of yourself — is not this grand concept that belongs on a pedestal,” says Amy. “It’s not sort of a permanent state that you reach eventually in your life if you work at it long enough. No one ever reaches a permanent state of presence. It’s impossible — because we’re human, and there are always thoughts that are poking through. So I ask people to step back from that stereotype of presence that became popular in the last part of the 20th century and think of it instead as something that occurs in moments.”

To tap into the full potential of presence, Amy says we should focus on those moments that are the most stressful — which tend to be high-stakes situations that involve some component of social evaluation. It’s about being authentic, but not in an unfiltered way — being deliberate without being deceptive.

“If you think back over your life to your best moments, who were you in those best moments and how can you be that person more of the time?” asks Amy.

The Price of Presence — Amy’s Story

The turning points that change the course of our lives don’t always identify themselves as turning points in the moment. It’s most often in retrospect that we can point to the overall factors that led to where we are today.

When Amy is asked about the turning point that brought the concept of presence to the forefront of her attention, she’ll say there were a few. But the main one was the car accident in college that left Amy functional, but minus 30 I.Q. points. Doctors told her she was lucky to be alive, along with other nuggets of, as Amy tells it, “insensitive feedback that you hear physicians giving people in movies.”

They couldn’t tell Amy if she would ever fully recover, and chose to err on the side of caution that she might not rather than give her false hope. This isn’t because they were cruel or incompetent; current medical science simply can’t provide a reliable recovery timeline for most brain injuries in the same way it can for a broken arm or a sprained ankle — the repercussions of a brain injury won’t necessarily show up on a scan.

But whatever the future had in store for Amy, she suffered what many other victims of traumatic brain injuries experience — not just a loss of I.Q., but a loss of identity.

“You’re different in every way,” recalls Amy. “The way you think is different. The way you feel is different. The way you move may be different. It affects your vision. It can affect your speech. It’s everything. And so you have really lost your former self to some extent, and for a lot of people with traumatic brain injuries, I think it’s very common to feel a sense of lost identity — and not even remembering what your former identity was, so it’s very hard to reconstruct.”

Body Language and the Presence to Cope with Fear

Amy did make it back to school, though it took her four years longer than originally intended because processing information became such a challenge. She started to look at presence as a way to counter the dread and anxiety she went through on a daily basis in the classroom — but this also didn’t come easily.

“Before doing something like giving a talk in class, my response was not in a normal range of nervous,” says Amy. “It was like a frightened animal that’s about to be attacked by a tiger. And that’s not adaptive. I was not able at all to be present. I was totally distracted by messing up. By what everybody thought of me. By what it was going to mean for my future. I was just in a death spiral in my mind as I was doing these things. I was everything but present.”

One of the keys to becoming present, Amy discovered, was in rejecting the body language that accompanied her fright. Rather than shrinking like a cornered animal at the first sign of trouble, she found that opening up her posture and forcing her body to take a stance of confidence invited a confident mental state. As we say often here at The Art of Charm: the mind follows the body and vice versa.

Cultivating Presence for Ourselves

Listen to this episode of The Art of Charm to learn more about how we can gear ourselves to think and act in the present rather than mulling over the future consequences of poor performance, how incongruence can clue you in when someone else is being inauthentic, why arrogance betrays insecurity instead of acting as a proxy for confidence, how inauthenticity exhausts cognitive bandwidth, why extroverts don’t have an unfair advantage over introverts when it comes time to command presence, practicing the components of presence so they become habits, how hunching over our smartphones and computers all day puts us into a posture of depression and powerlessness (and how using power poses in private helps us shake this effect — with scientific evidence to back it up), the difference between social power and personal power, the power of real self-affirmation, why trust needs to come before confidence and strength, and lots more.

THANKS, AMY CUDDY!

Resources from this episode:

- Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges by Amy Cuddy

- Amy’s TED Talk: Your Body Language Shapes Who You Are

- Amy Cuddy’s website

- Amy Cuddy Community at Facebook

- Amy Cuddy Community at Instagram

- Amy Cuddy at Twitter

- Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking by Susan Cain

- How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are by Brene Brown

- Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert

- Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from Dear Sugar by Cheryl Strayed

- AoC Episode 392: Simon Sinek | Start With Why

You’ll also like:

- The Art of Charm Challenge (click here or text 38470 in the US)

- The Art of Charm Bootcamps

- Best of The Art of Charm Podcast

- The Art of Charm Toolbox

- The Art of Charm Toolbox for Women

On your phone? Click here to write us a well-deserved iTunes review and help us outrank the riffraff!